Understanding the complexities of behaviour involves delving into the relationship between

actions and their triggers. Behavioural science often employs structured approaches to

decode these intricacies, shedding light on how patterns form and evolve over time. Among

these methodologies, the ABC analysis emerges as a cornerstone, providing a framework

for dissecting the components of behaviour through the lens of antecedents, behaviours, and

consequences.

This is a scientific method used to determine the function of the operant variables linked to a

behaviour. The analysis consists of three components: A-B-C, or Antecedent, Behaviour,

and Consequence.

According to S.G. Friedman, the ABC analysis is a process of observing a situation,

identifying what occurred prior to the behaviour (antecedent), and understanding the result

(consequence) to modify the behaviour. To simplify, it can be likened to a recipe, where all

ingredients and methods are provided, but an unexpected event may change the outcome,

such as pages sticking together, altering one’s response to the situation.

A functional analysis assesses and identifies the trigger preceding the behaviour and

determines the appropriate course of action. This is achieved through meticulous

observation of environmental factors, trigger points, and patterns that led up to the

behaviour.

For example:

A = Antecedent (Dog in the back seat of your car)

B = Behaviour (Dog barks incessantly)

C = Consequence (Dog is removed and placed in the front seat)

Result: The dog desired to be near its guardian in the car. Placing the dog in the back seat

(antecedent) resulted in barking (behaviour). Unable to tolerate the barking, the guardian

moved the dog to the front seat (consequence), thereby giving the dog the attention it

sought.

Another scenario involves addressing the function of a behavioural issue driven by fear. For

instance:

Problematic Behaviour: The dog pulls aggressively on the lead when passing a

specific house or gate because previously, the resident dog barked from behind the

gate.

Procedure for addressing the behaviour:

This requires a structured approach to identify and mitigate the triggers causing the

problematic behaviour, ensuring a more manageable outcome.

To address this behaviour, a desensitisation and counterconditioning protocol can be

employed. Start by identifying the threshold distance at which the dog begins to exhibit signs

of fear or anxiety, such as pulling or barking. Gradually decrease this distance over time

while ensuring the dog remains calm.

Introduce positive reinforcement at every step: reward the dog with treats, praise, or toys

whenever they exhibit calm behaviour near the house or gate. Pairing the previously feared

location with positive experiences can help alter the dog’s emotional response. Additionally,

work on redirecting the dog’s focus using cues, like “look at me,” or “let’s go” to help them

associate the triggering situation with constructive behaviour instead of fear.

Consistency, patience and empathy are key in this process, as well as ensuring the dog

feels secure and supported throughout the training. Over time, this method can help reshape

the dog’s behaviour and reduce their fear-driven responses.

The behavioural diagnostic delves deeper into the functional analysis, examining physical

and behavioural factors that may affect the dog’s behaviour. Key variables include breed-

specific behaviours, chewing or self-mutilation, fear of people/animals/places, history of

abuse, illness, pain, and medication side effects. Understanding these factors helps identify

the problem behaviours and their causes, allowing for an effective solution or modification

plan.

When conducting behavioural diagnostics, it is crucial to record observations objectively and

without bias. Focus on the behaviours themselves, not your interpretations or judgments.

Example Case: Functional Analysis and Behavioural Diagnostics

Genetics

Breed-related behaviours like flushing out small animals and chasing moving objects

Self-Stimulation

Light chasing

Chasing leaves

Operant Variables

Accessing reinforcers

Escaping from being on a lead

Sensory stimulation (e.g., scents)

Early History

Lack of training

Fear of certain dog breeds due to past attacks

Medical/Physiological Causes

None

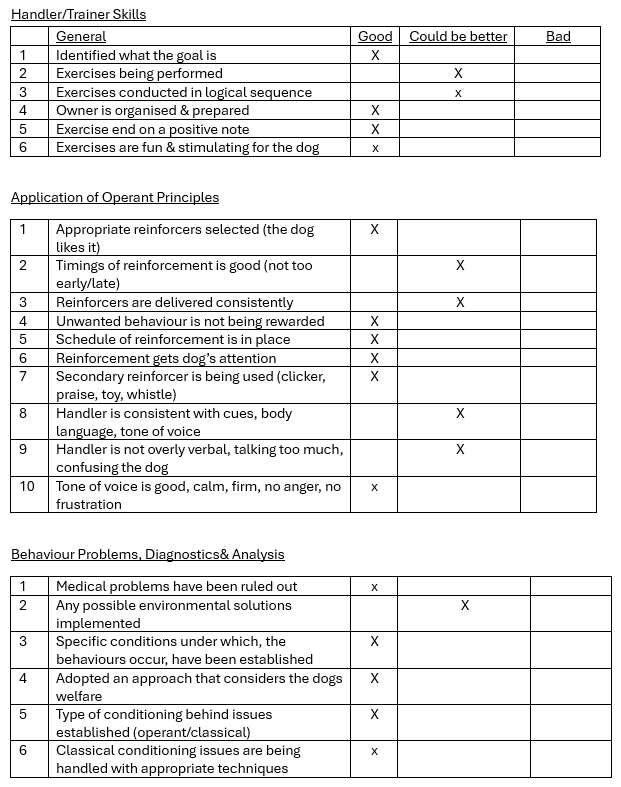

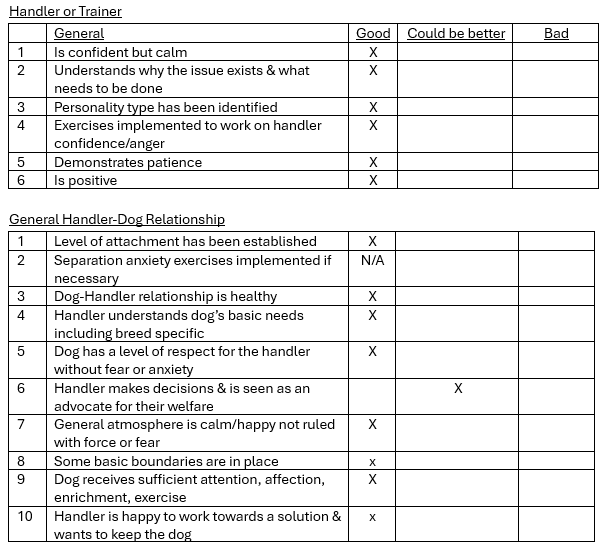

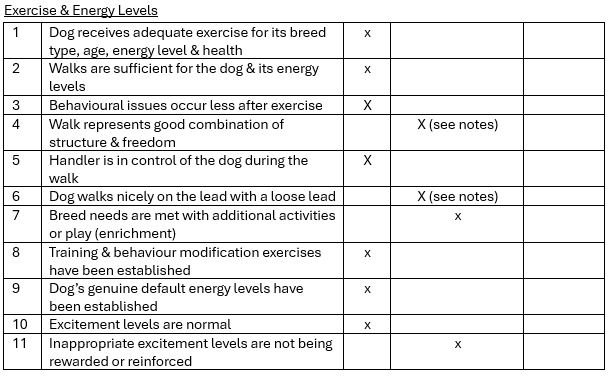

Below is an example of a skills form for the above case with the implications for the results,

along with a summarised suggestions for general improvement